01 Sep Swallowing Assessment for Head and Neck Cancer Survivors: Expectations and Outcomes

Written by Bonnie Martin-Harris, PhD, CCC-SLP, BRS-S

It doesn’t take an expert in swallowing disorders to inform a group of head and neck cancer survivors and their families that impaired swallowing is one of the most common, yet frustrating, results of medical and surgical treatments used to target cure for head and neck cancer. The extent of the swallowing problem will depend on the size and location of the tumor, the extent of the surgery, nature of reconstruction, and field and dose of radiation therapy. Adding chemotherapy to the treatment regimen may also increase swallowing problems. These outcomes are not purposeful, but rather side effects of the necessary cancer treatment. Significant advances have been made to lessen these side effects, such as new radiation techniques reducing the field and dose of radiation treatment. The head and neck region is compact and houses multiple nerves, muscles, connective tissues and blood vessels so the ability to shield structures close to the tumor target is difficult. Surgical scarring and radiation (combined with chemotherapy) may cause immediate restriction of movement to structures critical for swallowing function or these restrictions may occur years after the cancer treatment occurred. Restriction of movement and concurrent impairment of sensation (the ability to normally feel and taste the presence of food or liquid in the mouth and throat), interfere with airway protection, lead to aspiration (entry into the lungs), and/or hinder the ability for structures to push swallowed material from the mouth through the throat and into the esophagus.

Swallowing includes a series of complex, quick movements involving the tongue, pharynx (walls of the throat), larynx (voice box) and esophagus and occurs in approximately .5 – 2 seconds depending on the consistency and volume of the liquid or food. The following is a list and description of the critical components necessary for safe, efficient and comfortable eating and drinking:

- Lip Closure – the ability to contain liquid and food within the mouth and prevent drooling.

- Tongue Control – the ability to contain food and liquid within the mouth by elevating the front, sides and back of the tongue to contact the hard and soft palate.

- Mastication – the ability to breakdown and moisten food during chewing with salivary enzymes and organized movements of the tongue and mandible (jaw).

- Tongue Movement – the ability of the tongue to progressively apply pressure to the tail-end of swallowed food and liquid to propel the material through the mouth.

- Initiation of the Pharyngeal Swallow – the ability of sensory end organs in the tissues high in the throat to recognize the presence of food and liquid and relay the message to the swallowing center in our brain to command the muscles of swallowing to begin movement.

- Hyolaryngeal Movement – the ability of the larynx (voice box) to move upward and forward to close the valves at the top of the airway and pull open the top of the esophagus.

- Soft Palate Movement – the ability of the soft part of the palate to elevate and move backwards to prevent food and liquid from entering the nose

- Pharyngeal Contraction – the ability of the very base of the tongue to move backwards and contact the forward and inward movement of the walls of the pharynx (throat) to generate pressure to move food and liquid from the throat into the esophagus.

- Esophageal Clearance – the ability of the muscles of the esophagus to contract (squeeze) from top to bottom to move food and liquid into the stomach.

Despite the number of swallowing components that may be impaired after cancer treatment, there is some plasticity built into the system so that if one or some of the components are impaired, another component learns to take over the role of the impaired component. This learning often requires swallowing therapy with a speech-language pathologist who has specialty training in dysphagia (swallowing disorders) related to head and neck cancer. Swallowing therapy involves targeting the impaired components identified during a complete swallowing assessment.

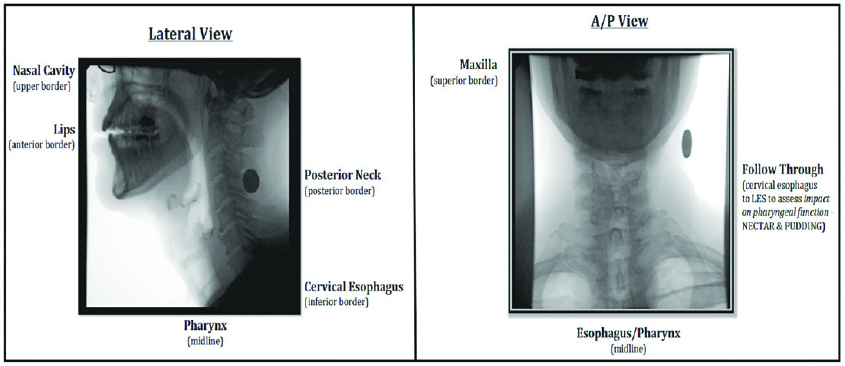

An initial clinical evaluation should precede and inform about the need for an instrumental imaging assessment of swallowing and airway protection. The clinical assessment includes examination of movements and sensation of the face, mouth and throat, and may include introduction of some liquid consistencies and food types depending on the severity of the swallowing problem. The ideal instrumental swallowing assessment, especially when conducted to inform decisions about oral intake (feeding tube placement, feeding tube removal, significant change in liquid or food consistency, or to measure the outcome of a cancer treatment or swallowing therapy) should include viewing swallowing in its entirety from mouth to stomach, whenever possible. This assessment is termed a Modified Barium Swallow Study (MBSS) and uses live videofluoroscopic (x-ray) imaging that examines all critical components of swallowing in real time (Figure 1).

Most MBSS are conducted in a collaborative manner between a speech-language pathologist and radiologist, each bringing specialized expertise to the procedure and outcome. Objective measurements of swallowing should be included using tools that have supportive evidence for clinical validity (meaningfulness), are able to be reproduced and interpreted by clinicians with similar training and that minimize radiation exposure and aspiration. A standardized protocol using commercially tested barium consistencies, swallowing tasks, swallowing instructions, measures and quantitative reporting to your physician should be included in each exam. At your request, digitized videos and understandable, written reports of MBSS results should be supplied to you and your referring physician and made available to other members of your care team from the hospital to home. We have come a very long way in understanding swallowing impairment using MBSS over the past 15 years. The examination you receive should follow the current evidence, have standard procedural expectations from facility to facility and the results should inform your plan of care.

It should be emphasized that a primary purpose of any swallowing evaluation is to guide swallowing therapy conducted by a speech-language pathologist. The therapy that is applied should be based on its effectiveness as demonstrated in the literature, should be personalized to the specific disorder(s) presented by the patient, and include face to face (in person or remote) instruction until the patient has achieved the maximum benefit from therapy. Further, even long after initial therapy has concluded, patients should be followed periodically by the speech-language pathologist to monitor the stability of swallowing safety and need for additional therapy because of the potential for late, negative side effects of radiation +/- chemotherapy treatment.

Unfortunately, not all swallowing impairments can be reversed or improved in cases of profound impairment. But if an alternative to oral intake is suggested to you, you should demand to understand the rationale for a non-oral feeding recommendation. Fortunately, many swallowing impairments can be improved using advanced swallowing rehabilitation methods. However, these methods should directly target the impaired components that have been objectively evaluated using MBSS. Other examinations such as fiberoptic endoscopic swallowing studies (FEES) may also be used in between MBSS to evaluate the functional efficiency (presence of residue) and safety (airway protective) effects of swallowing therapy methods that target the mechanism of impairment.

There is no good reason why any patient should not have access to the essential assessments and treatments they need for optimal care, including swallowing assessment. Patients should challenge their physicians, hospitals, insurance companies and speech-language pathologists to supply state of the art imaging methods for accurate diagnosis and safe and proven procedures for treatment. These essentials are critical for your safety and development of an effective plan of care.

Editors Note: Dr. Martin-Harris is the Alice Gabrielle Twight Professor in the Roxelyn and Richard Pepper Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders, Otolaryngology Head & Neck Surgery and Radiation Oncology, and Director of the Swallowing Cross System Collaborative Laboratory at Northwestern University. Dr. Martin-Harris’ clinical and research interests include speech and swallowing impairment and treatment approaches for patients with head and neck cancer, neurologic and pulmonary diseases. Dr. Martin-Harris is a member of SPOHNC’s Medical Advisory Board.